Shortly after 6 p.m. on Friday, convicted double-murderer Stephen Stanko was executed by lethal injection at the Broad River Correctional Institution in Columbia, South Carolina.

The execution marked the end of nearly two decades of legal proceedings surrounding one of the most brutal crime sprees in the state’s recent memory. Yet even in death, Stanko’s case remains a focal point in the intensifying debate over South Carolina’s execution protocols.

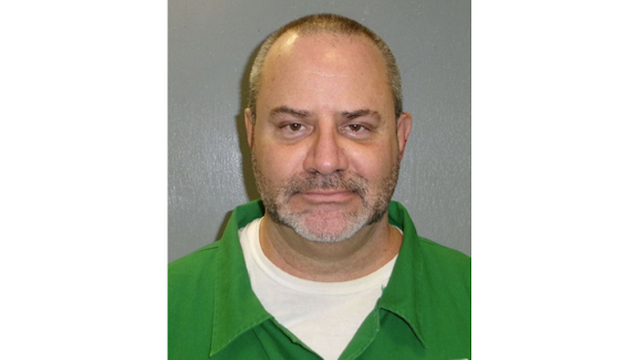

Stanko, 56, received two separate death sentences—an uncommon legal outcome—stemming from his 2005 murders of librarian Laura Ling in Georgetown County and his friend Henry Turner in Horry County.

During a chilling 24-hour crime spree, he strangled Ling in her Murrells Inlet home, raped her teenage daughter, and then slit the girl’s throat. Though severely injured, the girl managed to crawl to a phone and dial 911.

Fleeing the scene, Stanko drove to Turner’s home, where he murdered the 74-year-old with a single shot to the back—fired through a pillow as Turner stood in front of a mirror. Stanko stole Turner’s money and truck, sparking a multi-day manhunt that ended in Augusta, Georgia.

Before the murders, Stanko had served eight years of a ten-year prison sentence for kidnapping a former girlfriend in 1996. In that case, he had bound and gagged her with a bleach-soaked rag. Ironically, during his time behind bars, Stanko was regarded as a model inmate.

He wrote letters to local newspapers advocating for criminal justice reform and co-authored a book with two professors about life in prison. Upon his release in 2004, he moved to the Grand Strand area and began dating Ling.

Though he sought to continue his writing and find stable work, court filings suggest he became entangled in fraudulent schemes that were about to unravel at the time of the killings.

Experts at trial described Stanko as intellectually gifted but psychologically disturbed. His teachers recalled a bright, disciplined student in Goose Creek, but a series of traumatic brain injuries—beginning at birth and followed by sports-related concussions and an incident where he defended a classmate—had left him with damage to the brain’s frontal lobe.

Psychologists testified that the injury impaired his emotional regulation, leading to dangerous impulsivity and an absence of empathy. Though his attorneys claimed he was legally insane at the time of the murders, jurors in both trials were unconvinced.

As Stanko’s execution approached, he and his attorneys filed a sweeping constitutional challenge against South Carolina’s capital punishment procedures. Their arguments centered on recent concerns over both the electric chair and the firing squad—the state’s two legal methods of execution.

According to court documents, Stanko would have preferred the firing squad but feared suffering a prolonged and painful death. That fear was rooted in the April 11 execution of Mikal Mahdi, in which only two of three bullets reportedly hit their mark. Mahdi appeared to continue breathing for more than a minute after the shots were fired, and his autopsy revealed only two bullet entry wounds.

Left to choose lethal injection, Stanko’s legal team raised alarms about inconsistencies in the state’s drug protocol. While the South Carolina Department of Corrections has publicly stated it administers a single five-gram dose of pentobarbital, autopsies of previous executions showed that two men had each received ten grams.

Attorneys argued that this discrepancy—combined with findings of pulmonary edema, a condition causing fluid buildup in the lungs and the sensation of drowning—suggested the process was unconstitutionally cruel.

In a federal court hearing just two days before the execution, corrections officials admitted for the first time that their protocol includes a second dose if a heartbeat remains after ten minutes.

Due to state secrecy laws, lawyers for other death row inmates say they cannot fully assess the safety or legality of South Carolina’s execution methods, leaving unresolved questions about transparency, oversight, and human rights.

Stephen Stanko’s death closes a dark chapter in South Carolina’s criminal history, but the debate he reignited around capital punishment is far from over.